VITA has been working on numerous specifications that implement some of the new fabric technologies coming to market (InfiniBand, RapidIO, StarFabric, etc.), both on traditional VME boards (VITA 41) and on pure fabric architectures (VITA 34). Primarily, this work consists of choosing a high-speed differential signal connector (2.5 Gbits/sec and above), developing and testing the pinouts for signal integrity, and completing the mechanicals for the connector and the board. Unfortunately, we have hit some snags.

When a sanctioned standards developer like VITA choose a connector for inclusion in an American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standard, we must insure that any patents on the new device will be licensed under Reasonable And Non-Discriminatory (RAND) conditions. The connector vendors supplying the VME Switched Serial (VXS) and V-34 connectors agreed to RAND conditions during the selection process. But shortly after the connector decision, an outside company asserted their IP against the V-34 connectors (USP 6,379,188 B1). That company has decided NOT to license their IP under RAND conditions. At the VITA Standards Organization (VSO) meeting in January, the group removed the chosen V-34 connector and restarted the connector evaluation process. If a standards group chooses a connector that involves IP and that IP is not licensable under RAND conditions, then the standards group has violated anti-trust laws by creating a monopoly or duopoly.

The patent asserted against the ZD connector is a very broad patent concerning differential-paired high-speed connectors. The VSO evaluated prior art against this patent, but did not have enough to jeopardize the validity of the patent.

The VSO now has three options:

- Find another connector that isn’t covered by the asserted patent

- Create a "black box" specification that defines the connector envelope and electrical behavior

- Create a completely new connector that will be IP-free, and allow all connector manufacturers to make the connector royalty-free

The breadth of the patent on differential-paired connectors is very broad. The VSO will be evaluating several connectors that may be outside the coverage of the patent. However, the holder of the patent may believe that these other connectors also infringe on their IP.

Creating a black box specification for the connector would ignore the existence of the patent. The standard would simply require users to select a connector that meets those requirements. This would satisfy the anti-trust requirements (for example, not creating a monopoly or duopoly by specifying a connector that does not offer RAND conditions). Furthermore, the market of manufacturers would decide what specific connector is used. But this could cause incompatibilities in the market.

Creating a completely new connector that is IP-free will be very difficult. Even if the VSO could write a specification that avoids the asserted patent, there are many other patents on such connectors that have not yet been granted (patent applications are not visible for 18 months from date of filing).

This particular patent has the potential of affecting every single activity that develops industry standards for high-speed, differential-fabric architectures, whether they are ANSI-accredited committees or consortia. If we cannot find a connector solution that does not infringe the above patent, market acceptance and deployment of new fabric-based architectures could be delayed by many years. Worse yet, there could be no open standards for fabric architectures and the market for those new technologies would become extraordinarily fragmented with very little compatibility.

The connector industry has been severely affected by the downturn in the economy, particularly in telecom. The highest volumes of connector shipments for many years were to the telecom industry. With business conditions at historic lows, connector vendors are using their patents to differentiate themselves, to gain market advantage, and to capture large percentages of new, high-margin market segments like the new fabric architectures. The business issues and the motivations of the patent holders are very clear here.

VITA is not the only standards developer affected by this patent. Other consortia developing telecom-centric fabric architectures have the same problem. For the next few VSO meetings, the group will evaluate replacement connectors that are proposed as non-infringing. If the IP is asserted against those devices, then the group will have to develop the black box connector specification for the standard and allow the market to choose the connecto. At this stage, that seems like the only solution to this very sticky problem.

But, once we can solve the IP issues with the connectors, I fully expect to see many patents associated with fabric-oriented architectures emerge. There may be IP associated with SERializer/DESerializer (SERDES) techniques, with how switches behave, how certain architectures are hooked together, and how certain transactions are accomplished. So, even if we solve the basic connector IP issues, we could then be facing a number of other IP issues from the systems and silicon level.

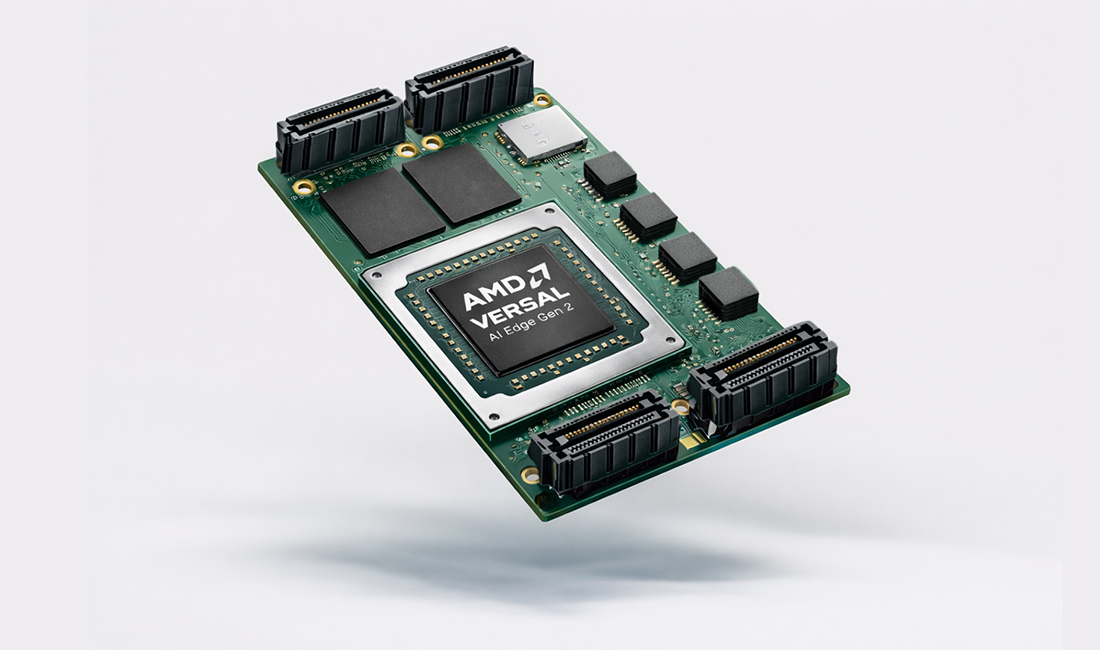

We see great interest in InfiniBand, RapidIO, and StarFabric in the VME markets, from both users and manufacturers. We will certainly see interest in PCI Express when it arrives. New silicon devices are coming tomarket spurring much R&D effort with fabric technologies. These new technologies and architectures could be the catalyst for renewed growth and prosperity for system builders in many depressed market segments like telecom. But until we can find a solution to the IP problems, the risks manufacturers and users will face from IP assertions are unacceptable.

This is a very creative industry. I think we will find those needed solutions, and the development of fabric-based products and markets can resume without fear of expensive IP assertions. If you have any suggestions, we would love to hear them.